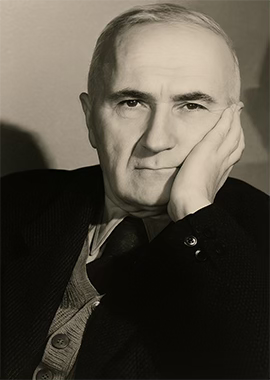

Born to a peasant family in a small village in Western Georgia, and expelled from Kutaisi high school for taking part in the 1905 revolution, Dimitri Uznadze’s experience situated him in a world of disrupted authority, unmet needs, and collective tension. Expectation and belief, as he would discover, were drivers of action before conscious reasoning can kick in.

Beyond psychology, Uznadze also published works in philosophy, education, and history, reflecting his broad intellectual interests. But it was his seminal work on the “Theory of Attitude” (or “Set”) that went on to gain worldwide recognition in 1939, after an article of his was published in the Dutch scientific journal Acta Psychologica, which was friendly to theoretical and experimental ideas. With it, he argued that behavior is shaped by an unconscious state of readiness, formed by needs and expectations, that influences how we perceive and act.

The original term in Georgian, used by Uznadze and his followers, is “განწყობა.” In Georgian literature, both “attitude” and “set” can be translated into this same word. In English-language psychology, “attitude” usually refers to a stable trait, while Uznadze focused on situational attitudes or “sets”, temporary states shaped by current needs and context.

Uznadze, in his opening paragraph, presents a foundational example to explain why perception isn’t shaped by raw stimulus [1]:

As is well known, in 1860 Fechner reported an illusion that became known in psychological literature as the weight illusion. It is formulated as follows: “If a heavy weight is lifted very often, the lifting impulse becomes so ingrained that it still takes effect after 24 hours, with the result that another weight that is lifted appears too light.”

In the weight illusion there’s evidence of carryover from prior experience, rather than sensory error on its own. The motor set is the pre-established lifting impulse, or pre-conscious expectation prior to picking up the weight. Uznadze generalizes this and transfers it from weights to everyday perception and action. The difference between readiness and reaction shows that we don’t meet the world fresh each time.

Uznadze extends this logic beyond perception. By itself, a need only produces action when a situation makes fulfillment possible. Hunger, for example, doesn’t automatically generate the impulse to eat unless food is realistically available. Without that context, no psychological set is formed [2].

At the same time as Uznadze’s article in Acta Psychologica, mainstream psychology was treating humans as stimulus-response machines (e.g., Skinner). Inner states were either ignored or treated as unscientific, but the Theory of Attitude said something intervenes. Between stimulus and response sits a pre-existing readiness, shaped by past experience, that biases perception and action before awareness. That let psychologists talk about internal structure without abandoning experiment.

To address the elephant in the room, it’s important to at least briefly pit Freud’s approach against Uznadze’s. The father of psychoanalysis famously put the unconscious at the center of psychology, but mostly through interpretation and clinical stories. Uznadze treated the unconscious as something you could create in an experiment and observe through its effects, without relying on psychoanalysis. While their lives overlapped over many decades, the year that Theory of Attitude was presented was the same year the Freud died, so he never had a chance to critique or comment on it. However, the criticism in the other direction did occur [3]:

Uznadze was ambitious enough to claim that Freud’s understanding of the unconscious is flawed and the Freudian term unconscious should be replaced by the set.

The reach of the theory extended beyond perception studies. In an article in 1944, Jean Piaget referred to the phenomenon describing the visual field illusion as the “Uznadze effect” and drew on it in describing stages of intellectual development, placing Uznadze’s work within mainstream twentieth-century psychology [4]. It also exists in a middle ground in twentieth-century psychology, since it’s neither behaviorist nor psychoanalytic. His idea of set is a reminder that perception and action are always shaped in advance, by history as well as stimulus.

Sources

1 - Untersuchungen zur Psychologie der Einstellung (Acta Psychologica, 1939)

2 - Reconsidering the “Uznadze Effect” and Psychology of Set (Gantskoba) From a Systemic Cultural Psychological Perspective

3 - Alternate Unconscious: Uznadze’s Theory of Set (video version)

4 - Basic Points of the Anthropic Attitude Theory