When was the Georgian alphabet created, and what gave impetus to its creation? These questions have long concerned Georgian society, because the Georgian alphabet itself represents one of the main pillars of Georgia’s statehood and its cultural heritage. Georgian writing played a crucial role in the unification of the Georgian people and in the formation of a single state [1].

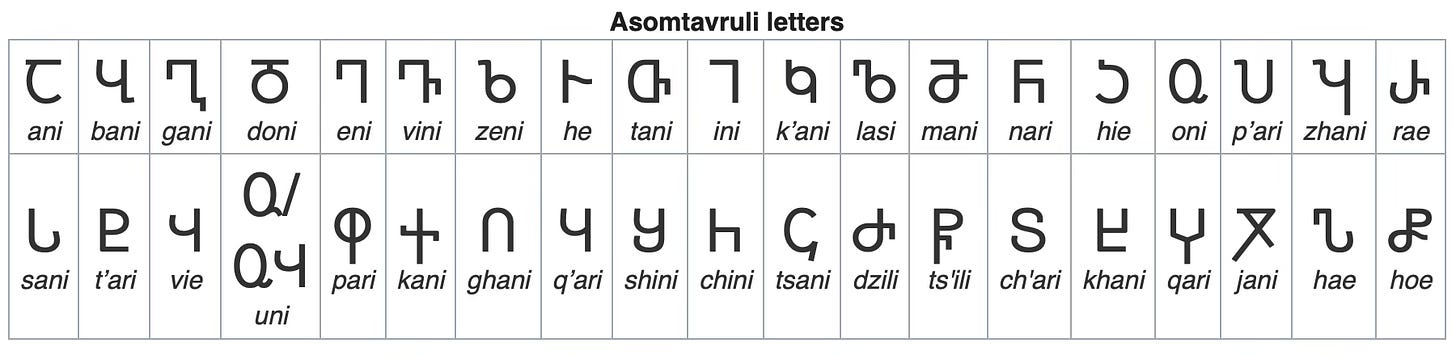

Asomtavruli, meaning “capital letters”, is the oldest of the three Georgian scripts and goes back to at least the early 5th century. It was created with only one case (ie, no lowercase) since carving onto stone and clay were the only forms of preservation at a time when authority mattered and literacy was limited.

When the Caucasian Iberia1 was Christianized in the 4th century under King Mirian III, the Georgian script likely emerged along with it. Some scholars argue that writing in the region may have existed earlier, in the pre-Christian era, based on mentions in Greek and Roman sources and analyses of Asomtavruli letter forms [2]. Its use was initially for translation purposes, when monks converted the Bible into Georgian.

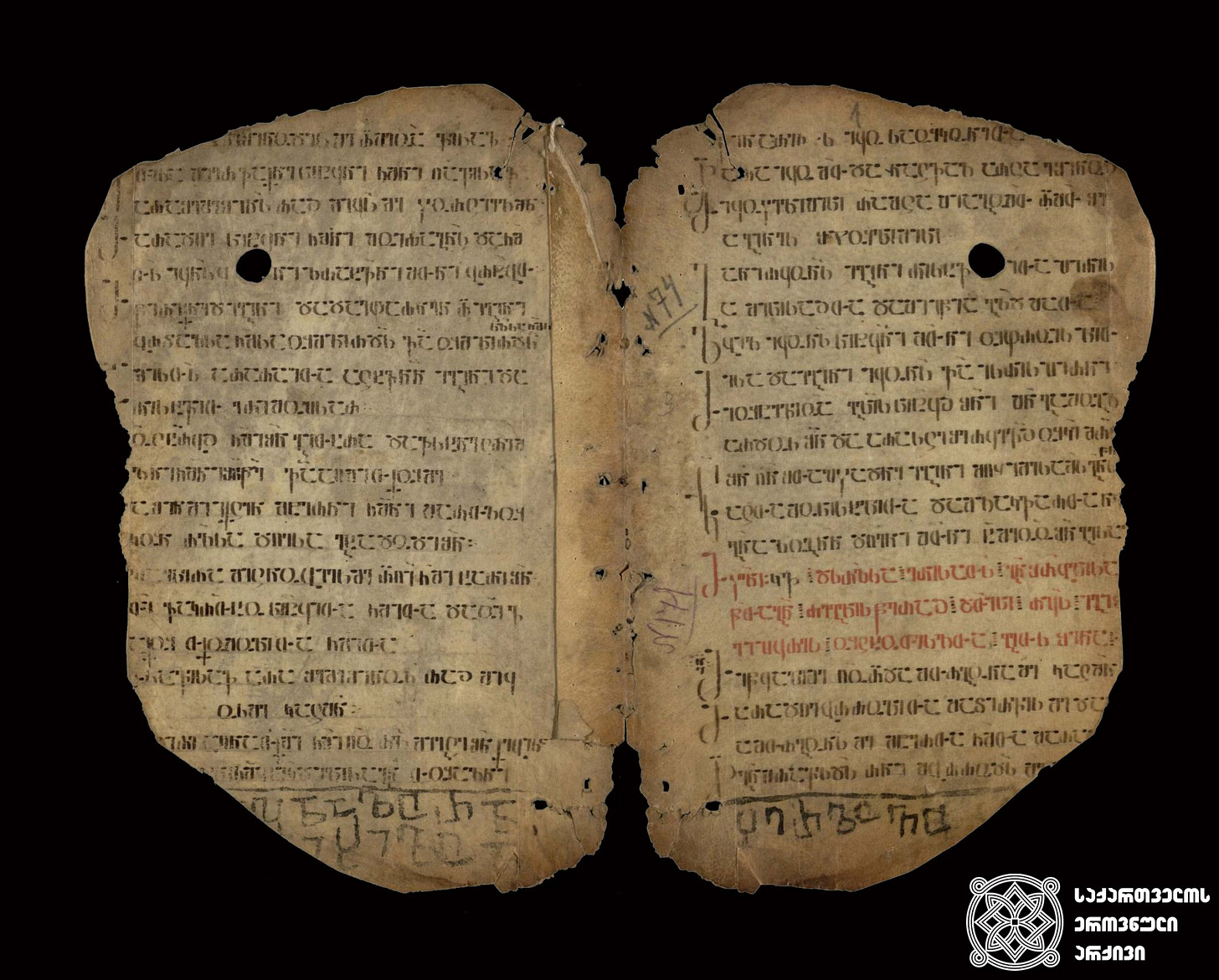

Because parchment was scarce and costly, early Georgian manuscripts were frequently reused. Even though the first Georgian texts were “serious” theological works, monasteries still removed older writings to make room for new ones. Earlier translations might be replaced by outdated versions or simply sacrificed to meet the immediate need for copying new texts.

The oldest layers of Georgian writing survive mainly as palimpsests2, not because they were unimportant, but because they were written early enough to be overwritten later. The earlier writing isn’t truly gone, as it survives faintly underneath and can sometimes be recovered with careful study or modern imaging. These palimpsests - preserve archaic editions of the Holy Scriptures, Christian liturgy, hagiography, and hymnography - are the oldest evidence of Georgian writing and language, dating back to the 5th-6th centuries [1].

Note: Armenians sometimes claim that linguist Mesrop Mashtots invented a script for the Georgians and the Caucasian Albanians as well as for themselves, but there is only corroborating evidence for Armenian.

Features of Asomtavruli

Asomtavruli is immediately recognizable by its large geometric characters. Its letters are round in overall shape3 and written at a uniform height, giving the script an all-caps appearance. Straight strokes are either horizontal or vertical and meet at right angles, making the script feel orderly and architectural.

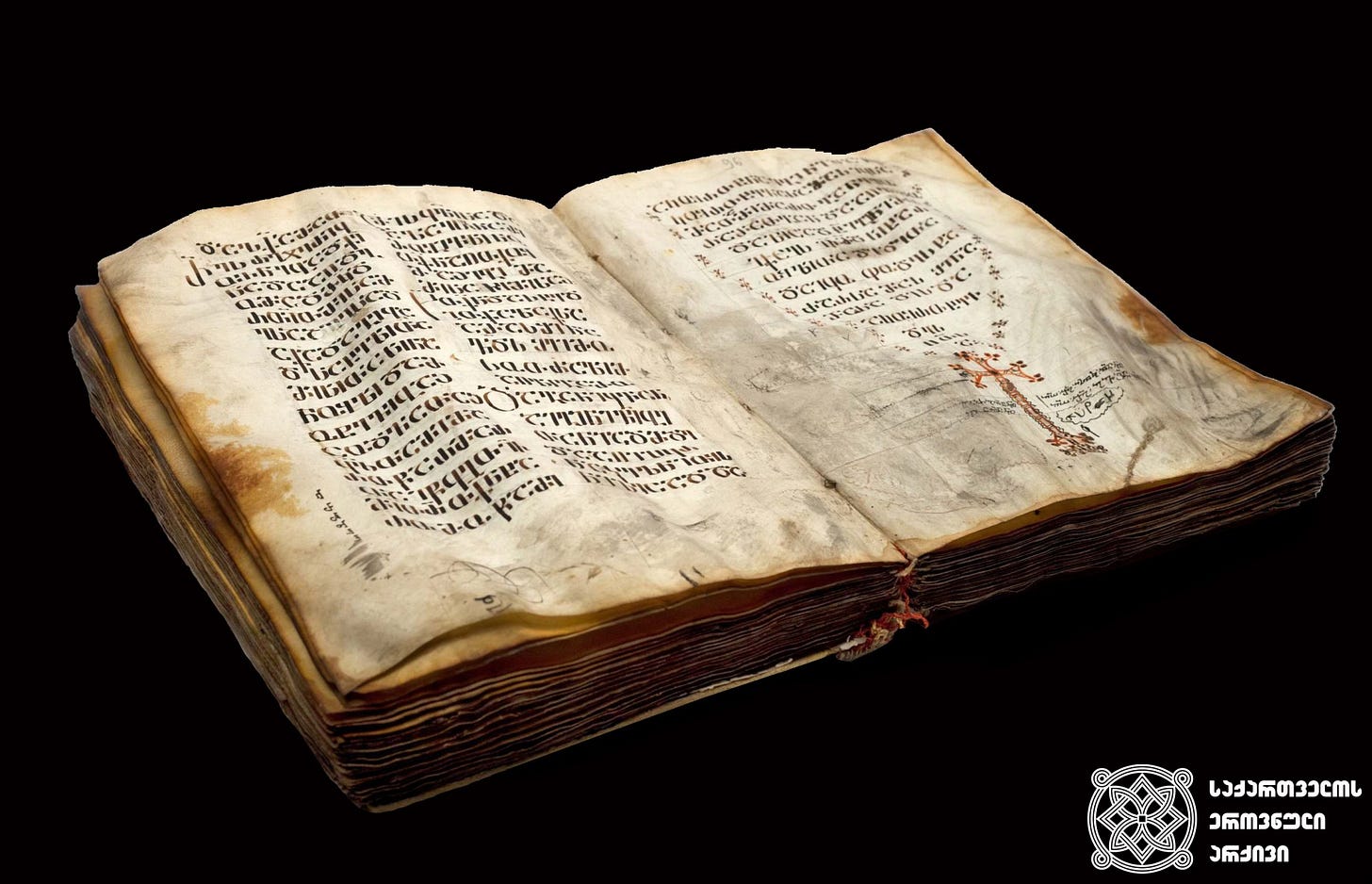

This uniformity began to relax from the 7th century, when some letter shapes started to change. The equal height of the letters was gradually abandoned as ascenders and descenders4 appeared. This change broke the rigid uniform manner of the script and made writing faster and more efficient, making way for later Georgian scripts.

Asomtavruli was used to inscribe monuments and manuscripts from the 5th to the 10th centuries. From the 9th century onward, the angular Nuskhuri (lowercase) script developed alongside it and increasingly became the dominant writing form for manuscripts [3]. As this happened, Asomtavruli took on a more specialized role. In texts written in Nuskhuri, it was reserved for titles, headings, and initial letters, where its large, formal shapes served a decorative and emphatic function (often being illuminated or highlighted with red ink).

Although its everyday use declined, Asomtavruli didn’t disappear. Monuments continued to be written in this script up until the 18th century, at which point it became even more ornamental. By then, Asomtavruli took on the role of signaling tradition and authority within Georgian written culture. All three of the country’s scripts are now enshrined as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, and the Georgian Orthodox Church uses all of them, with its spiritual leader calling on people to use them all, too. In this way, Asomtavruli reminds Georgians that their written language is alive and connects them through culture and faith.

Additional information

1 - The Creation of the Caucasian Alphabets as Phenomenon of Cultural History

Sources

1 - V–XIX საუკუნეების ქართული ხელნაწერი მემკვიდრეობა (plus a truncated English version)

2 - Georgian Unique Alphabet

3 - The three lives of the Georgian alphabet

a Greco-Roman exonym for the Georgian kingdom of Kartli

a manuscript page where the original text was scraped or washed off so the material could be reused

thus why it’s also known as Mrgvlovani, which means “rounded”

strokes rising above (like b, d, h in Latin) or falling below (like p, q, y) the main body line