In the mid-20th century, Soviet development plans demanded the reinforcement of the banks of Tbilisi’s main river, the Mtkvari. Long before embankment walls went up, the capital was home to several islands, both large and small, as well as a dense landscape of Iranian-style gardens that structured leisure, sociability, and movement beyond the city proper. In 19th-century Tbilisi, recreation was not organized around plazas or parks in the Western sense, but around cultivated garden spaces embedded both at the city’s edges and within its neighborhoods.

Sololaki Gardens (pre-1795), along with 19th century green spaces such as Alexandrovski Garden1, Mushtaidi2 and Ortachala functioned as seasonal escapes and social filters, often reflecting class divisions more clearly than neighborhoods did. In this sense, Tbilisi was a city of gardens - heterotopias, to use Foucault’s term - where ordinary social boundaries were temporarily loosened [1, 2].

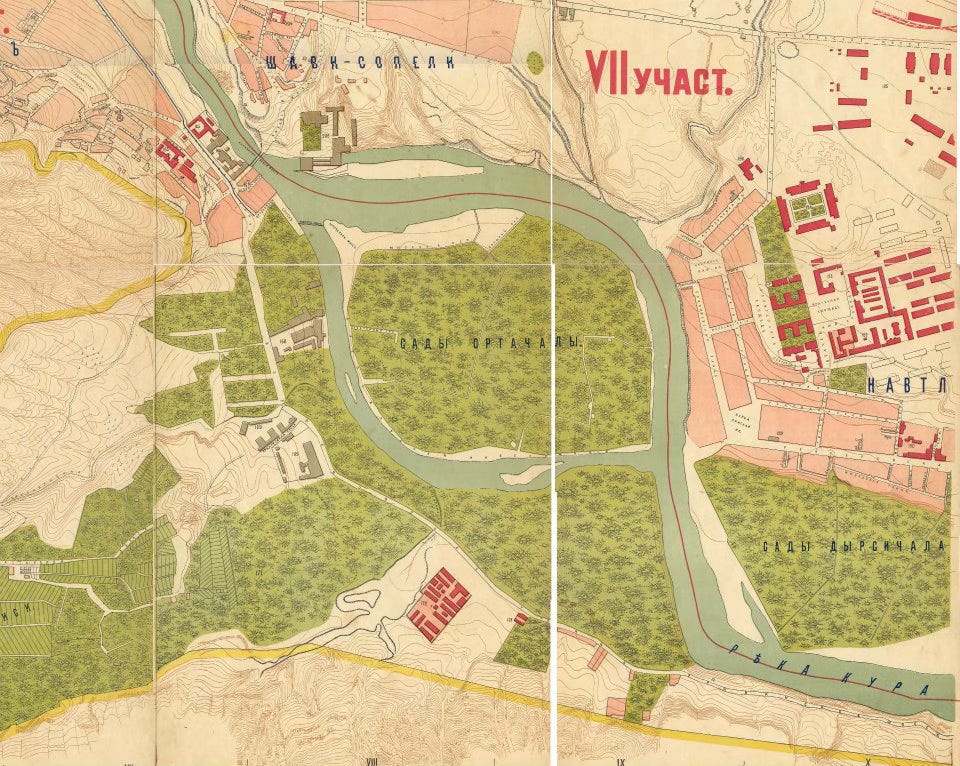

The largest and most well-known of them - Ortachala Island - sat where the river split into branches, just south of the city. The first time it was given a name was in 1735, on the map of Prince Vakhushti Bagrationi, the Georgian geographer and historian. There, it appears as the Krtsanisi Garden, named after the nearby district of Krtsanisi to which the land was administratively attached. Following the death of King George XII in 1800 and the removal of Prince David Batonishvili from Georgia one year later, the royal gardens passed out of dynastic hands. At first, they were ecclesiastically owned and, soon after, entered into the hands of Tbilisi’s merchant class.

A threaded commons

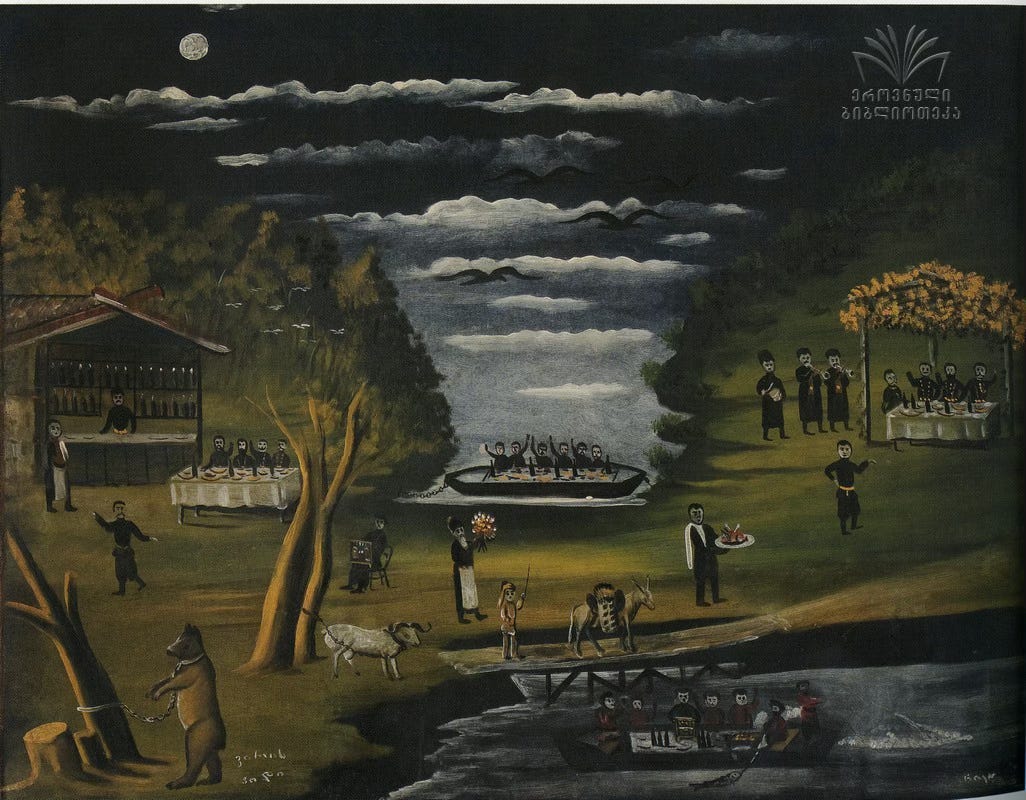

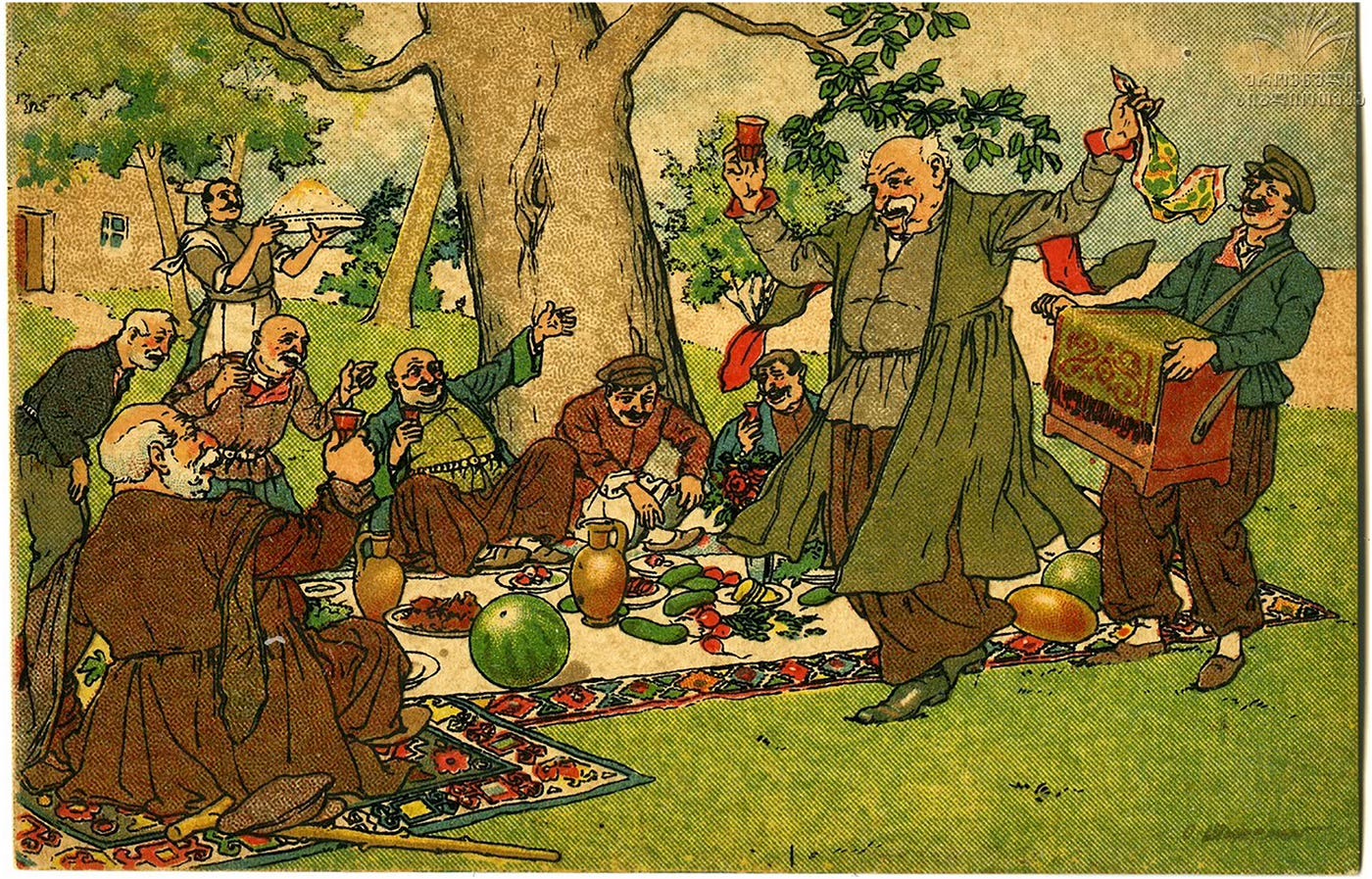

At Ortachala, leisure took a distinctly urban-folk form, with Tbilisians arriving by carriage and on foot with tethered sheep and wineskins filled with Kakhetian wine. Groups gathered for long picnics, music drifted from duduk and daira3, and ashugh poetry was passed along orally before ever reaching the page. By the 19th century, literary recitation was already part of the atmosphere; in the 1920s, this evolved into open ideological clashes between the Symbolist Blue Horns and emerging proletarian writers. In effect, Ortachala was a social stage: noisy and intellectually alive, but also a working landscape, its orchards and kitchen gardens supplying the city each morning. The produce was carried into the city across a bridge, by donkeys, which came to be known as the “Donkey Bridge”.

This “meadow between waters,” as its etymology suggests, was neither a royal park nor a fully public square. It could best be explained as a commons threaded through private plots. The area consisted of individually owned gardens - often belonging to merchants or gardeners - linked by informal paths. Social life unfolded in a semi-public way: gatherings took place by invitation within particular gardens, yet movement between plots, taverns, brothels, and eating houses kept Ortachala open, noisy, and broadly accessible.

An 1869 article titled “A Stroll Through Tbilisi,” best captures the feeling [3]:

What could compare to this poetic disorder, this irregularity - the vine trellises, the pleasant scent of tall walnut trees heavy with foliage, the eye-catching and mouth-watering variety of fruit, and finally the ear-awakening creak and grind of the waterwheel? Now a song, now the duduk, the daira, cool mulberries, cherries… How could the above-mentioned gardens compare to this, with their evenly planted trees and walkways tamped down with crushed brick, where you wouldn’t even find a rug or a small cushion to lie back on for a moment or bend your knee?

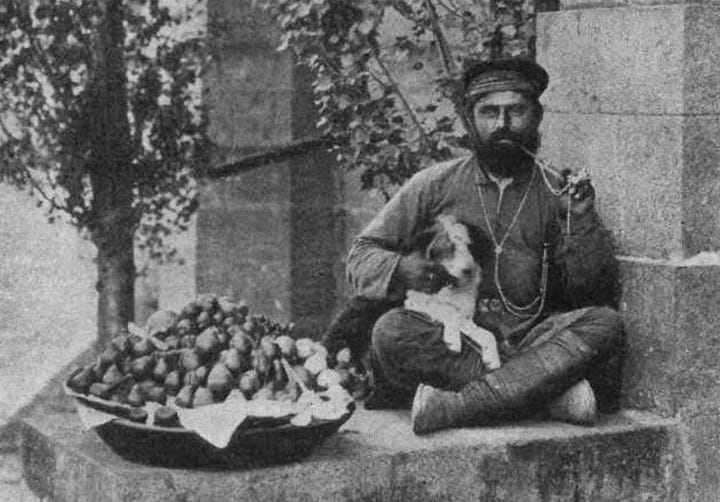

Among the recurring figures of Ortachala was the kinto: a small-scale street trader who moved through Tbilisi’s streets selling fruit and other goods from a tray or handcart. The figure emerged from Iranian urban traditions and appeared in Tbilisi during the period of Persian rule, taking on its familiar shape in the 19th century. Quick on his feet, verbally agile and socially marginal, the kinto belonged to the world of petty trade rather than to the city’s civic or craft traditions. Later folklore, especially in the Soviet period, often blurred this figure with the qarachoğeli, an older urban type of Georgian origin associated with honor and public standing [4].

Beyond his role in the city’s economy, the kinto also served as a convenient poetic stand-in, allowing aristocratic authors to describe urban pleasure without speaking in their own voice. Poetry of the period rarely described “coffee houses, baths, markets, balconies, courtyards, and squares” directly; instead, it circled gardens, feasting, music, and leisure, often voiced through the lowlife trader [2]. The “I” in such poems was vicarious rather than autobiographical, a form of ventriloquism not unlike the cantigas de amigo of medieval Galicia, where male poets wrote in a female voice.

The qarachoğeli, by contrast, was a rooted urban type of Georgian origin, tied to craft guilds (amkari) and neighborhood life rather than to itinerant trade. Artisans in Old Tbilisi were organized into these guilds, each trade having its own, headed by a senior master. The amkari functioned not only as a professional association but also as a form of social security, regulating production, overseeing workshops, enforcing obligations, and protecting members’ rights. Typically an artisan or small shopkeeper, the qarachoğeli was known for physical presence, bravado, and a public code of honor. Unlike the socially marginal kinto, he occupied a recognized place in the moral economy of old Tbilisi, and the two figures were mutually antagonistic, reflecting the divide between guild-based craft life and precarious petty trade. Qarachoğelebi were frequent figures in Ortachala, famed as singers, revelers, and wrestlers [5].

Conclusion

Ortachala was never just a garden suburb or a site of leisure. It was a working landscape and a social commons, where irrigation canals, vineyards, and market gardens coexisted with music, drink, poetry, and spectacle. Figures like the kinto and the qarachoğeli moved through this space in different ways, embodying the textures of old Tbilisi’s urban culture.

Little of this world remains. Behind modern buildings, faint traces of Ortachala’s nineteenth-century bohemia still surface: ruined bathhouses, fragments of brick pools, and the foundations of old inns and taverns, overgrown and slowly fading. With the construction of the Ortachala Hydropower Plant in the 1950s, the embankments, and later urban development, the river branch was erased, the island disappeared, and the gardens that once sustained both leisure and livelihood gave way to high-rise housing. What survives is largely historical memory. Ortachala is no longer a place to be entered, only one in which, as Grigol Orbeliani wrote, he once saw himself, across the social and emotional life of the city.

Additional information

1 - სად მდებარეობდა ლეგენდარული ორთაჭალის ბაღები - ზურა ბალანჩივაძის რუბრიკაში „ეს იცოდით?“ [6m]

2 - Rivers of Tbilisi – a Brief History of the Urban Center’s Relationship with its Waterways

Sources

1 - Public Parks of Tbilisi (pdf)

2A - The City of Gardens: Three Garden Heterotopias of Old Tbilisi

2B - The “Poetic Chaos” of Gardens and Genres in Colonial Tbilisi

3 - ორთაჭალა - National Parliamentary Library of Georgia

4 - კინტო – kinto

5 - ჟურნალი “ისტორიანი”, 2013 წლის მარტი, ნომერი #3/27

6 - ფოტოამბავი: როგორ გამოიყურებოდა ცნობილი “ორთაჭალის ბაღები”

British traveller in 1896: “Here at times an excellent military band discourses music, and all the fashionable world of Tiflis parades. It is difficult, then, when walking under shady trees, surrounded by a well dressed European crowd, to imagine oneself in an Asiatic town.”

roughly the area of today’s Mziuri Park / former Hippodrome–Vake edge, near the Vere River. In the 19th century it was a landscaped garden associated with European-style leisure - promenading, concerts, cafés

local traditional instruments