Before Georgia had a printing press, Georgian books existed almost entirely as manuscripts, copied by hand in monastic centers such as Mount Sinai in Egypt and the region around Jerusalem. Yet the first book ever printed in Georgian did not appear in Georgia at all, but in Rome, in 1629.

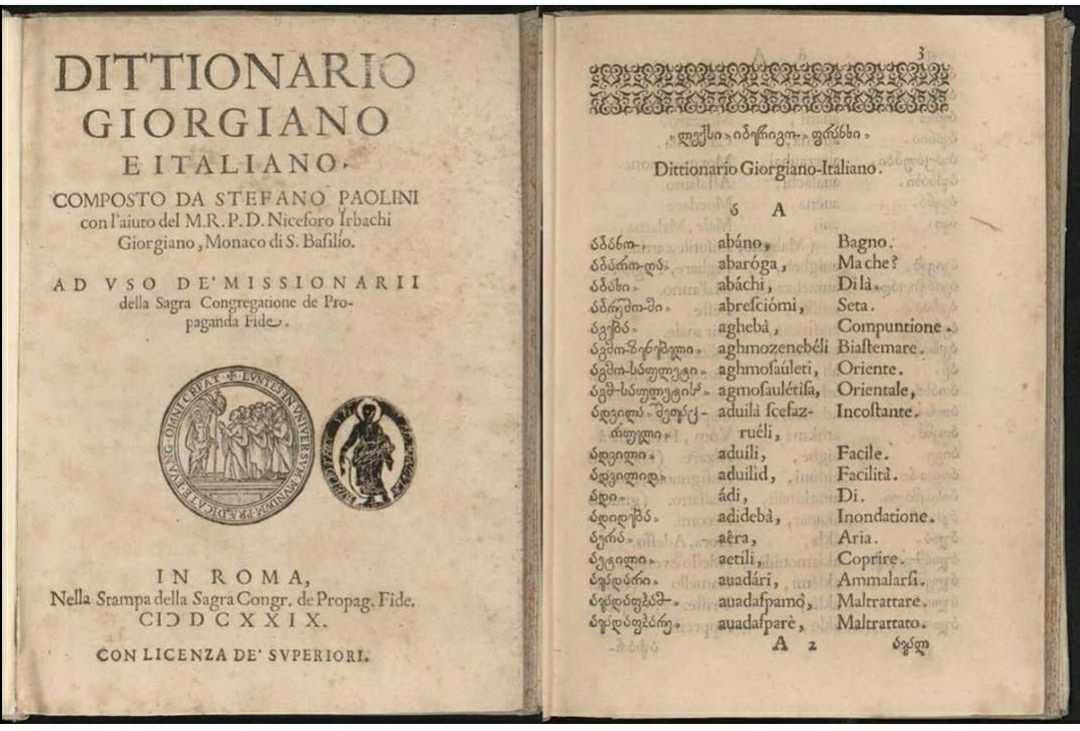

As the first-published work by the newly-created Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, or Propaganda Fide, the Dittionario georgiano e italiano was created to help missionaries with the Georgian language and spread Catholicism in non-Catholic countries such as Georgia. It’s important to note that Georgia has been Christian since the early 4th century and Eastern Orthodox almost continuously, so Propaganda Fide’s goal was conversion, not support of an existing Catholic church.

The dictionary itself is more functional than literary. It is divided into three columns: the Georgian word, its Latin transliteration, and the Italian translation. Although early criticism focused on errors supposedly caused by the compilers’ distance from the language, later research suggests a more complex production process. Georgian Ambassador, Nikifor Irbach, appears to have provided the Latin transliterations but was not in Rome for the entire compilation. The Georgian script itself was likely added by linguist Stefano Paolini, while a Greek translator was also involved in preparing the text. This helps explain the inconsistencies1 in the dictionary, without reducing the book to simple incompetence [1].

The initial efforts of the Holy See led to Italian priests studying Georgian and being sent to the Caucasus, with the end result of producing the first book of Georgian grammar. As one article on the origins of Georgian printing notes [2]:

Until the 19th century, these books were the only sources through which Western European scholarly circles became acquainted with the Georgian language. Moreover, through their publication, Georgians sought to break through the hostile Muslim encirclement and to re-establish connections with the Western Christian world.

From the start, Georgian printing took shape outside Georgia, through exile and diplomacy.

Kings commissioning type

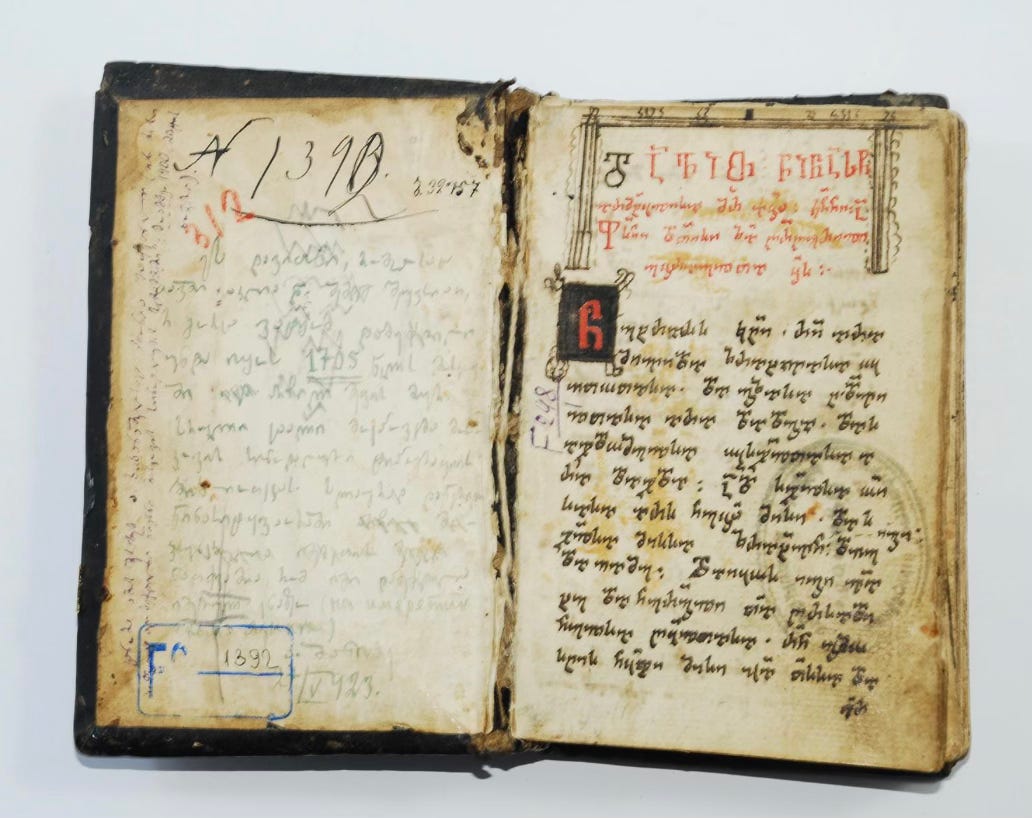

The next book in Georgian was a product of exile when, in the 1680s, King Archil of Imereti requested the assistance of intermediaries. This led to renowned Hungarian typographer Nicholas Kis being commissioned to make Georgian typefaces out of Amsterdam, which included asomtavruli, nuskhuri, and mkhedruli letters. The result was that in 1705 the first Georgian book of Psalms - the “Davitni”, or Psalms of David - was printed in Russia [3].

A mere few years later, in 1708-09, through the efforts of King Vakhtang VI of Kartli, it was finally possible to create the first publishing house in the country. The needed technical equipment was brought in, via Bulgaria, thanks to printers Mihai Ishtvanovich and Antim Iverieli. One of the first books published in “Vakhtang’s Printing Press” was the 12th-century epic poem The Knight in the Panther’s Skin (Vep’khistkaosani) by Shota Rustaveli. In all, 19 books - mostly religious - were the first to be published not only in the Georgian language but in Georgia itself, that is, until the Turkish invasion of 1722 put a halt to things.

It wasn’t until 1749 that, through King Heraclius II, the printing press could be restarted but, by 1795, it was destroyed along with the entire city of Tbilisi due to the Persian invasion. This on again, off again relationship with printing, in Georgia and by Georgians, was due to the dozens of invasions and major campaigns by foreign armies, over several centuries.

Georgian print culture was both resilient and fragile, emerging in bursts rather than as a continuous tradition. Read together, these episodes explain why Georgian literary life remained manuscript-heavy long after the printing press had transformed Europe. Printing failed because each attempt was shaped by exile, invasion, and interruption. Yet the repeated return to printing speaks to a persistent determination to preserve language, assert political agency, and anchor cultural life in a written tradition of their own.

Sources

1 - Saqartvelos Biblioteka 2020 (pg 14)

2 - ქართული ბეჭდური წიგნის სათავეებთან

3 - From Soviet to European Copyright: The Challenges of Harmonizing the Copyright Legislations of Post-Soviet Non-EU States with the European Copyright Law (Georgian Case)

47 Greek words appear in the Georgian column of the dictionary